Lumber Grade-Marking History: 1923

Introduction

1923 was a year of famous firsts. In February, the American Law Institute was incorporated. In March, the first issue of Time Magazine was published. In April, Yankee Stadium – which only began construction just one year prior – was ready to open its doors, just in time for opening day. Not only did the Hollywood sign make its notable first appearance in California in July, but Roy and Walt Disney also founded The Walt Disney Company in October. Prohibition still raged across the country, but as a nation, we weren’t about to let that stop the incredible progress we were making.

1923 was many things, but it was also among the most important in the entire industry of the Southern Pine Association – as this was the year that grade-marking machines were finally perfected. This, in turn, gave way to the successful development of a comprehensive, holistic plan to establish the practice of grade-marking lumber across the country.

In this section, you will find out more about notable concepts like the McDonough Branding Machine. You will track the wave of progress as it makes its way across the south, through states like Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, and Georgia. You will also learn more about the expansion of the Southern Pine Association throughout all of this, as its increasing membership numbers were quickly seen as hard and firm evidence that grade-marking was finally ready for prime time, so to speak. We hope that you will find it informative and compelling, two qualities that people of the time no doubt shared.

1923

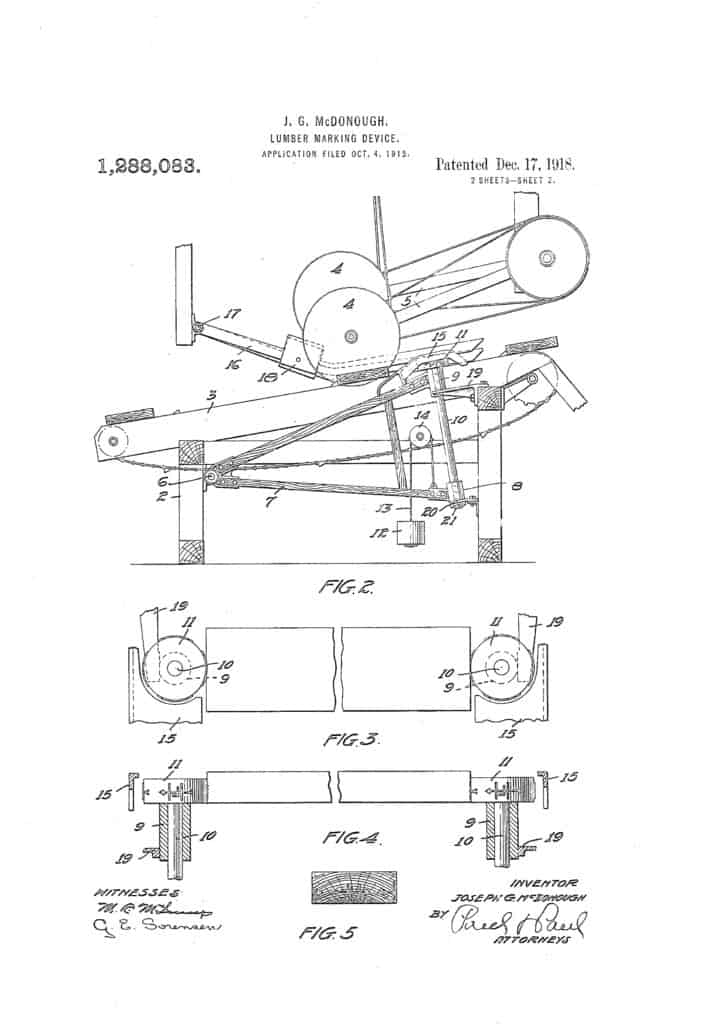

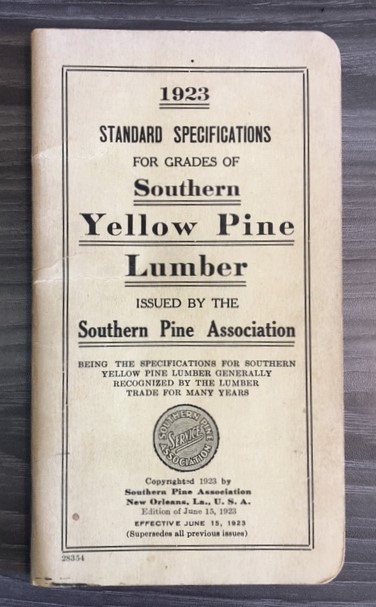

The most tangible, conspicuous and concrete accomplishment of the Southern Pine Association for the year was the perfecting of a grade-marking machine and the successful development of a plan to establish the practice of grade-marking lumber. Through prior cooperation, the McDonough Branding Machine had been improved to operate economically and efficiently. Installed for trial at Oakdale, Louisiana, the machine ran satisfactorily and continuously, marking lumber from a matcher for several months. The cost was 15¢ per M and was considered subject to reduction, as skill was acquired, to 10¢ per M. With proof that the machine was the kind of automatic unit wanted for volume work, it became necessary to negotiate a contract between the patent holder (J.G. McDonough) and the Southern Pine Association for the exclusive rights to use the machine in grade-marking southern pine in the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. Some form of outright payment for the machine was sought, but not available. An arrangement on a royalty basis of 1/2¢ per M, with contingent provisions, ultimately satisfied the patentee McDonough. Officially received as satisfactory, acceptance was acknowledged on October 11, 1923. The cost of building one of the machine grade-marking units was still problematical, as to specificness, but estimated to be about $225 or $300 per unit.

Impressed that the marking of lumber for the purpose of certifying the grade was a conception, the growth and application of which was a progressive step of the lumber industry, the Southern Pine Association was credited by industry with originating and making practical use of the idea. Mechanical handling of the lumber marking process was considered essential to its success. The machine for so doing had been discovered, improved and purchased. Intensive organization work remained to make grade-marking effective with producer, consumer, and the intermediate wholesalers and retailers. 50% of the Southern Pine Association subscribers were desired as evidence of willingness to adopt the practice – 72% consented – and it was then thought prudent to have unanimous approval. The greater the volume, the less the cost of manufacturing and installing the branding machines, and the lower the cost of servicing their operation and productions. Lumber dealers, wholesalers, contractors, engineers, architects, and the consuming public many of whom had already endorsed grade-marking were seeking additional information, and some departmental form of organization among the manufacturers using grade-marking was required to attend to the routine. Cost of such work was placed at not more than 1¢ per M, including branding machine use royalty. Considered ample to cover accomplishment of grade- marking as a policy in the industry, merchandising and advertising as a plan to increase sales was an additional subject for early study.

The exclusive right of subscribers to use the McDonough Branding Machine had been contracted for by the Southern Pine Association – insofar as southern pine was concerned. Limitations for use of the machine by subscribers only were not intended as an industry restriction; but by retaining exclusive rights to use of the machines in branding southern pine lumber, the Southern Pine Association was in position to more fully guarantee to the consuming public that they were receiving and could receive southern pine properly graded and specified. Otherwise, indiscriminate use of grade-marking machines might defeat the very situation the movement attempted to correct. Delivery to consumer use of the grade specified properly determined under standard rules at the time of manufacture, and unmolested by middleman handling and delivery, was the basic reason for grade-marking. Continuous vigilance by the Inspection Department of the Southern Pine Association was deemed advisable, and to accomplish consumer protection lawful control of the grade-marking machines became fundamentally necessary.

No profit motive or angles of monetary gain existed. The Association considered building and buying the machines, under the exclusive feature of the contract with patents, and leasing them to its subscribers at a price equal to the actual cost. Subscribers who withdrew from Association activities were not obligated to conform to standard grading rules or the Inspection Service and therefore were not entitled to use of the machines, although compensated for any money investment that they may have advanced for machine rental.

A summary report – the following – was officially approved by the subscribers of the Southern Pine Association:

…the subscribers to the Southern Pine Association, in annual session March 28 and 29, 1922, recommended the grade-marking of lumber, and

…72% of subscribers agreed to grade-mark their product when satisfactory mechanical means could be secured, and

…the task of soliciting suggestions for mechanical means of stamping, printing or impressing grade-marks upon manufactured lumber was entrusted to this Committee, along with the responsibility for perfecting a machine that would accomplish this purpose, and for securing the right to the use thereof, and

…the Committee has learned that Mr. J.G. McDonough and associates hold legitimate patents for machines to be used in the end-marking of lumber, and

…the Committee, in cooperation with Mr. McDonough, and under provisions of his patents, has succeeded in building a machine, which after severe trial has proved satisfactory, and

…Mr. McDonough has submitted a contract to the Association, containing many satisfactory conditions and providing for the payment of a royalty of one-half cent per thousand feet on shipments of all subscribers when and after 51% of subscribers represented by production have in their possession grade-marking machines manufactured from Mr. McDonough’s patents, and

…the Committee, after two years of close association with this problem, has become convinced that the grade-marking of lumber is possible and desirable, and that it will be productive of far-reaching results; it is therefore recommended:

That the contract be negotiated with Mr. McDonough under the terms and conditions outlined in this report, and

That those subscribers who are willing should cooperate in an effort to put grade-marking into effect, and

That a special assessment of 1¢ per thousand feet affective March 1, 1924 be levied upon those subscribers for the purpose of inaugurating a departmental activity to carry on the detail and mechanical work of securing machines and making surveys of individual mills to ascertain whether it is possible to economically and efficiently install and operate such machines, for the promotion of the grade-marking idea among those subscribers who may not agree to grade-mark their product and to expound the principles of grade-marked lumber to retail lumber dealers, wholesalers, contractors, engineers, architects and to the consuming public, it being understood

That the agreement to pay the special assessment of 1¢ does not bind a subscriber to grade-mark his lumber, but that all subscribers who contract with the Association for use of the grade-marking machines shall be obliged to pay the special assessment, and

That when the preliminary work of securing and installing machines at the plants of those subscribers desiring to grade-mark their product is accomplished, the assessment of 1¢ per thousand feet be continued to pay the royalty to Mr. McDonough and continuing such minor departmental work as may be necessary, and

That the Southern Pine Association exercise the exclusive right provided for in our contract with Mr. McDonough to the use of his machines only by subscribers to the Association, under the terms of lease providing for the reimbursement to the Association by each subscriber, of the cost of the machine leased to him, and for the discontinuance of the use of such machines and their disposal, should the subscriber cancel his general contract with the Southern Pine Association.

Retailers’ comments expressed satisfaction that the “grade juggler” was in line for elimination from the lumber business. Regarded as astonishing, the fact that lumbermen had for a long time overlooked the best bet in their industry – the one thing that would elevate them in the mind of the public, the grade-marking of lumber – the southern pine industry was the only large industry that paid no attention to the quality of its product after manufacture. It was admitted by retailers that there were many illegitimate wholesalers and retailers also, termed the “two timers,” who made unjust claims as to grade and tally against the manufacturer, and, in turn, by re-grading, “horse-traded” the consumer into accepting lesser value than to which he was entitled. By reason of these practices, both wholesaler and retailer who explained their sins as being those of the manufacturer, the general public did not have the right idea nor the correct knowledge of the lumber industry. Many things had been done superficially to overcome this condition, but public opinion persisted in condemning the industry, which remained idle in the matter permitting anyone who saw fit to damage their integrity. Grade-marking was considered the vehicle by which public opinion was to change for the betterment of both consumer and producer; benefits likewise accruing to the legitimate wholesalers and retailers.

The course of lumber from the conversion plant or manufacturer to the consumer appeared to be clearly defined. The manufacturer graded his lumber under standard rules and shipped full tallies. Once loaded and shipped, his order was complete and – “out of sight, out of mind.” Legitimate wholesalers and retailers received their merchandise, paid their bills, sold the lumber to the consumer who obtained the grade to which he was rightfully entitled. Frequently, however, this legitimate course encountered many obstacles, each rendering the originally intended rightful procedure of the manufacturer one of illegitimacy. On receipt of the loaded car, the illegitimate fellow proceeded to unload it – removing a few of the better pieces to cover the cost of his work in unloading the car, and further juggled the grade to accomplish the purpose of degrading the entire carload sufficiently to justify making claim for redress by the manufacturer shipper. His claim accepted, for no reason other than it being the easy way out, it was profit, although illegitimate. He then re-graded the carload of lumber, now his, putting the best of the shipment into a higher grade and letting the worst of it stay where it was originally. The wholesaler and retailer who had thus jug led the manufacturer’s legitimate shipment, then proceeded to offer the public the lumber as received, so-called, from the manufacturer, complaining, together with the consumer, that lumber “just naturally is not as good as it used to be.” The contractor may have entered into the circumstances affecting the consumer’s purchase, through the architect who had specified the lumber grades to be used in the building, and he (the contractor) decided a little grade juggling would be profitable to him also and unobserved by anyone else. Ultimately the original lumber shipments, properly graded, tallied and dispatched by the manufacturer in the first place, resulted, through the various grade juggling maneuvers, in the consumer not getting proper and due value. He expected the right kind of merchandise; but being the object of unscrupulous manipulations, he didn’t get it. He should have received lumber so marked at the originating point in the manufacturer’s plant, that he could be independent of misinformation and disarming conversation, or his own incompetent judgment, feeling assured that the mark thereon was sufficient and proper evidence that what he had was right. The grade-marking of lumber intended to accomplish this very thing.

While the Southern Pine Association as the lumber industry’s representative, by reason of the more substantial manufacturers being subscribers, favored grade-marking, there were non-subscriber manufacturers who regarded the effort as being too much trouble. With the money for their conversion processes in hand from whoever ordered the lumber, they were no longer concerned. What mattered the character of business the other fellow was in so long as he paid his bills? and, after all, wasn’t the consuming public better off for knowing less? Obviously, a necessity to enlist their cooperation to maintain harmony in the industry, selfish reasons for joining the grade-marking movement were pointed out as being of benefit to these non-conformers.

The disposal of low-grade lumber always was a manufacturer’s problem – the market could not use it or did not want to pay the price, it seemed. All lumber being good for some purpose or other, the user himself could determine the grade he wanted and buy that grade, if he would be permitted to judge the grade on its merits in the light of standard rules and his own requirements – uninfluenced by designing salesmen. Users or consumers would thus consider and buy the lower grades. On the one hand, he wasn’t buying the lower grades because, in the majority sense, these low grades had been marked up as higher grades, and the user misled to believe that there wasn’t any such thing as lower grades available outside of a sawmill plant. On the other hand, the user or consumer was unwittingly, in the majority sense, buying the lower grades under the styling of the higher grade, and on the higher- grade price basis. Irregardless of cost, if the lower-grade quality was sufficiently good for his use, with the higher-grade styling under grade juggling tactics, this same lower-grade quality, logically, was equally as useful and less expensive, with grade juggling and the coincident false styling eliminated. Lower grades would thus move from the manufacturer to the consumer by reason of the understanding of their usefulness and availability, not being interfered with by illegitimate middleman handling. The grade-marking of lumber appeared destined to correct this fallacious situation.

Some means of protecting the public both as to grade and tally in shipments was pointed out in the Hoover Conferences on Simplified Practice as being one of the things that industry should develop. Possibly Secretary Hoover obtained the suggestion from the several years of a previous effort by the Southern Pine Association, in this connection and possibly from the complications of “jerry building” arising with the public in the larger consuming markets. Whichever way it was, the situation was stressed to the point of emphasizing its importance and something would have to be done. The mechanical means was at hand and officially considered of decided advantage to industry and customer protection. This paved the way for further determinations.

Size standardization and simplification of grading rules and nomenclature were not a demand of the Department of Commerce through Secretary Hoover. Because of difficulties resulting from the substitution of grade in transit and other bad practices attributed to the lumber industry, Secretary Hoover, at the request of the lumbermen themselves, invited them to Washington for the conference. They went. They conferred. Included were manufacturers, retailers, wholesalers, engineers, architects, wood-working manufacturers, railroad officials, all-species representation from all parts of the country, Government bureau agents. Secretary Hoover stated that there should be simplified grade rules and nomenclature, standard sizes, and a means or method of guaranteeing to the public that they would get what the manufacturer sold and charged them for.

The thickness of one-inch boards and the finished width was the only major difference in agreement on standard sizes for national application. Freight rates operated to the disadvantage of the South because other woods originating at more distant points and having higher freight charges needed narrower widths and thinner boards in order to meet competitive prices in the larger industrial markets. Common nomenclature was agreed upon by the Manufacturers Committee of Standardization covering grade names of all species of wood, vis.: A, B, C, D, No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, No. 4 Common and No. 5 Common. These were the original designations of the Southern Pine Association (D and No. 5 Common excepted) and no change or adjustment by southern piners was needed, no D or No. 5 Common being existent. The nomenclature was already simplified insofar as they were concerned. Others were required to change. A one-inch board was agreed to dress 25/32. Southern pine made a concession and reduced their previous standard of 26/32 to 25/32, but retained their original standard of 13/16 or 26/32 as extra standard. Proceeding to the Consulting Committee of Standardization, where those concerned with the lumber manufacturer’s product had their way, the basic Manufacturers Committee report was approved and then passed on to the Central Committee of Standardization, where it was also duly approved and forwarded to Secretary Hoover and his Department of Commerce, where the original Manufacturers Committee report on Standardization was unanimously adopted.

Since southern pine was reducing its previous standard measurements to conform to standards desired for wood species from other regions of the United States, and at the same time was retaining its own previous standard measurements for use in trade, double standards came into existence for southern pine: one being standard lumber manufacture and the other extra standard lumber manufacture. Standard lumber manufacture became mandatory. Extra standard, while officially permissible, was not mandatory.

The subscribers of the Southern Pine Association adopted the standards and nomenclature of Simplified Practice resulting from the Hoover Conferences. Grade-marking was conceded to be the means of protecting and guaranteeing the public that the grade shipped was the grade ordered and paid for, unchanged since leaving the manufacturer. At the conclusion of this lumber conference, a second was decided upon to be held within the ensuing four months to handle the unfinished business of rough dry dimensions, short and odd lengths, grade-marking, and specific grading rules.